A lot of the work I do as a sex educator is in the college classroom. I haven’t taught a Human Sexuality class yet, or done a campus Sex Week yet, but in designing and teaching classes in anthropology, gender studies, and folklore programs, I emphasize many basic themes and topics in sex education, such as how sexuality, gender, consent, and sexual health are treated and transformed in culture and narrative.

One good example of this kind of teaching is how syphilis makes it way into my classroom (not literally – that would be a very different kind of lesson plan!). I’ll give two instances of this phenomenon.

When teaching a class on body art, defined broadly as any aesthetic adornment of or modification to the human body, we did a unit on plastic surgery. I lectured from Sander Gilman’s book Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery.

Most of my students were not aware that aesthetic (or plastic) surgery came about in large part due to the social stigma of syphilis. Becoming common in Europe in the 16th century* – and incurable til the 1940s – syphilis causes not only genital sores, but also a bunch of symptoms depending on how advanced it is:

- Rashes

- Fevers & weight loss

- Paralysis

- Disfigurement

- Blindness

- Dementia

- Death

To focus a bit on the disfigurement part, syphilis could be acquired through sexual activity, or passed on congenitally. One of the results is that someone could be born with it, and through no action on their part, be tainted by the social stigma of having it if they had visible signs of the infection: most notably, a caved-in nose (if the cartilage of the nose became infected and thus degraded). Having a too-short nose, then, or a nose that was obviously eroded, was a visual symbol for moral degradation, either that of yourself (if you contacted syphilis through sexual activity) or your parents (if it was congenitally transmitted).

As Gilman documents, European surgeons tried to come up with a way to fix people’s noses, and only had mediocre successes until the early 1800s. In 1794, a British army surgeon reported on a procedure carried out by a brickmaker in India, who used a wax model to recreate the shape of a man’s nose that had been amputated in war. The wax was placed on the man’s face, and a strip of skin brought down from his forehead to graft onto the area around the nose, securing the wax nose in place. This practice then spread throughout Europe, offering those ravaged by syphilis an opportunity to try to “pass” as moral, clean, and untainted citizens.

So, if you think aesthetic/plastic surgery is a neat development, you can thank the stigma of syphilis for prompting people to innovate. If you think plastic surgery is awful and ties into body image issues and heteronormative visions of female beauty, well, consider that these kinds of surgeries have helped people live lives free of shaming based on unwanted disease symptoms.

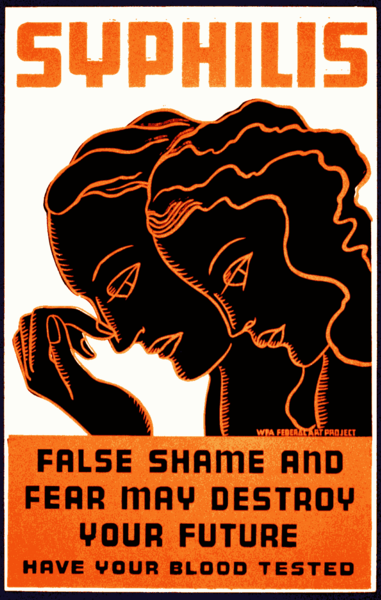

My second example of syphilis in the classroom comes from my class on sex education within/across cultures & histories. It’s a bit more of an obvious tie-in with this class, but the really interesting thing is how important syphilis was to the development of public sex education programs in the U.S. and across the world.

As mentioned above, syphilis was incurable until the 1940s, when penicillin was introduced. What was going on then? World War II. Perhaps more significantly, World War I had come and gone, and with it, the realization that VD (venereal disease, as STIs were called back then) was a major force in incapacitating soldiers.

According to this Mother Jones photo essay, The Enemy in Your Pants, during World War I the U.S. Army discharged more than 10,000 men because of VD. So, the military quickly realized that it had to not only provide prophylaxis – treating men for STIs after they returned to camp, in an attempt to counteract any disease before it got started** – but also education.

However, as Robin Jensen documents in her book Dirty Words: The Rhetoric of Public Sex Education, 1870-1924, these efforts were limited, biased, and exclusionary. White male soldiers received the most attention, with materials such as films and pamphlets distributed at their training camps. Black male soldiers received little. White women civilians were mostly kept in the dark to preserve their feminine purity, while black women got even less information.

One of the major results of the VD crisis in WWI, however, was the implementation of public sex ed programs in the civilian world. According to Jeffrey Moran in his book Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the 20th Century, the medical statistics gathered for the war effort were shocking: the surgeon general estimated that five of every six infected soldiers had contracted VD before entering the military.

Thanks to the intersection of war, syphilis (and to be fair, gonorrhea), and medical knowledge at the time, the social hygiene movement in the U.S. got a huge boost in its efforts to bring sex education to the public. Granted, sex ed at the time was still pretty puritan, enforcing terrible untruths about how men and women are totally different when it comes to sexuality, how women are the gatekeepers of purity, how men are sexual beasts, and so on (which, sadly, are still being taught in abstinence-only classrooms, as this recent tweeting spree demonstrates).

To wrap up this blog post before it gets any longer – can you tell I love this stuff?! – the intersections of culture and STIs like syphilis are fascinating and multilayered. In the body art example, we see how the social stigma surrounding syphilitic symptoms prompted the development of what would become a major surgical innovation. In the historical example, we see how it took a war for medical professionals in the U.S. to realize just how widespread of a problem VD was for the general population – and that everyone, not just white soldiers, was going to need better education to help fix the problem. And yet even after the advent of penicillin, we still have syphilis outbreaks, proving that we need not only better sex ed but also better access to information, protection, and medication.

*There is some debate as to whether syphilis existed in Europe prior to contact with the Americas. This article in the Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health examines the evidence, and provides a number of intriguing written testimonies from European history and literature about the effects and perceptions of syphilis.

**As Moran describes it: “Chemical prophylaxis at the time involved the laborious process of scrubbing the genitals, injecting a chemical solution into the urethra, and then wrapping the genitals for a while in calomel ointment and waxed paper. Performed competently and within a few hours of intercourse, the treatment was quite effective” (71). Sounds fun, eh?